My Reflection on the Great East Japan Earthquake

Written by: Koji Kohama

Early 50’s, gay and MtX, living in Taihaku-ku, Sendai.

Belongs to Tohoku HIV Communications (THC).

Also involved in Yarokko, a gay volunteer group which deals with the issue of HIV passed between men.

Nurse doing in-home care-giving and on-location nursing.

The condo building he lives in with his male partner of almost 20 years was partially destroyed, but his room was spared, and he lived there as a disaster victim.

Although I was asked to write from the perspective of someone in the disaster area, the term is rather broad and many points of view are contained within it. I will write about what I felt and experienced in my own way.

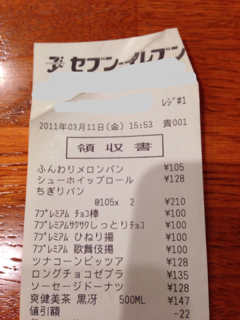

■March 11

It is March 11, 2011, and I am receiving professional training when the earthquake strikes during one of our class breaks at school. We are all in the classroom, and as my classmates all duck under their desks and hide I sit alone at my desk and hold on until the shaking stops. Thankfully there are no large objects in the room which could have fallen over, and the greatest damage was done by the clock falling from the wall and shattering. After the quake subsides, we decide that the old building is too dangerous for us to stay inside and we exit out the front. There is a large crack in the stairs and I feel afraid. The street is crowded with people who have exited the building as one after another aftershocks hit. I soothe my frightened school friends as I watch the scene. I receive a text from my partner saying that he’s okay, and I feel relieved.

The head teacher of the training school cautions us all to be careful as we go home, and I round up several people and head towards Sendai station. The station is jam-packed with people, who spill off the sidewalk and onto the street. The transportation networks are paralyzed and so I decide to make my way home on foot. On my way I try to text my partner repeatedly but I can’t get through. Reining in my impatience, I follow the Hirose River toward the south. Ahead of me I can see black smoke rising. It’s coming from the Yuriage district of Natori city. I wonder if there’s been a fire. Near my house a fire truck is announcing by loudspeaker that a tsunami over 10 meters tall is approaching and that we should move away from the river. The thought crosses my mind that the black smoke could be a fire caused by the tsunami. The snow begins to fall in earnest. An old woman from the neighborhood seems on the verge of tears as she cries, “Why does it have to start snowing now, of all times!” It’s dark now but the streetlights and traffic signals are unlit. The power is out. I arrive home to find all our possessions tossed about the apartment, but my partner has cleared out a space in the bedroom for us to stay. As we rejoice at finding each other unharmed, we bring out the kerosene heater which we kept for just such times as this, light it, warm ourselves by it, and cook some food. My partner tells me that while the water was still flowing he gathered some in a pot for us to use later.

■March 12

The next day, we go outside only to find that black smoke is still rising from the directions of Yuriage, Arahama, and Tagajo. I use a public telephone and somehow get in touch with my parents in Osaka Prefecture. We have absolutely no information, so I ride around the neighborhood on my bicycle. I learn that the elementary school is being used as an evacuation center. Upon arrival, I spy a newspaper extra displayed on the front windshield of a parked car, and I learn the true scale of the tragedy. On my way home I stop at a newspaper stand which is open and inquire after the extra, but they are completely sold out. The next day I head to a shop first thing in the morning and receive a newspaper. The proprietor is giving them out for free saying, “At times like this we all need information. Take it free of charge.”

My partner and I devour the contents of the newspaper, exclaiming in disbelief every now and then. That evening the power comes back on and we are finally able to watch TV, leading to even greater shock. It turns out that the black smoke was caused by the tsunami. The smoke rising from the oil combine at Tagajo shows no signs of stopping.

Early on, we obtain food supplies by visiting stores whose refrigerators have shut down and are selling off their inventory of foodstuffs cheaply before they spoil. After visiting several places we have an ample supply and can relax somewhat. Thereafter, even when we line up to enter a store, there is nothing remaining on the shelves. It’s not as though grandpa is cleaning up the house while grandma is out buying groceries, but my partner tries to tidy our quarters while I diligently travel hither and yon trying to procure supplies during the day. I am heartened that I am not alone and that he is with me. He says he feels the same.

I bike 30 minutes to visit the office where I work only to find the state of the rooms to be unbearable. The building itself, however, is still unharmed, and I resolve to keep in touch with my colleagues as we patiently await the city’s recovery. Before long the subway system is partially restored and community center ZEL, an operating partner of Yarokko, opens its doors right away. I prepare a box full of rice balls and cheerfully depart. I see my friends who have all overcome these hard times, and our conversation grows excited and lively.

Tohoku Shinkansen’s Max Yamabiko stopped atop the Hirose River bridge (photo taken March 2011)

■Sexual minorities at the time of the disaster

THC put its activities on hold, particularly its help line, until the end of April 2011. We continued providing information on our website (the status of the hospital we’re based out of and how to deal with withdrawal if one’s medicine runs out), but the members of Yarokko were instrumental in restoring the system for medical examinations thereafter. ZEL was able to continue operations, and Yarokko played a big part.

Around that time, there was a discussion on the internet about showing consideration for sexual minorities at evacuation centers. I caught glimpses of a movement trying to do what it could for sexual minorities in the disaster area, but being in the area myself I can’t deny that I felt out of the loop. To be honest, it was all I could do to get through each day and I didn’t have the wherewithal to think about what others were thinking. I finally mustered enough effort to post, “Please wait until you hear a call from the disaster area,” and nothing more. I don’t think I was able to really act until Rainbow Fund and Rainbow Aid began to take tangible action. In addition to Rainbow Aid, ZEL, ESTO, meetings on sexuality and human rights, THC, and other groups gave us various forums in which to speak about our relationship to the disaster. During those discussions, we were slowly able to verbalize the relationships among gender and sexuality, the disaster, and society.

■And now

After the disaster, I was barely able to continue my professional training somehow, and finished in September 2011. At the same time I took on a part-time home care-giving job, and afterward I began working in an on-location nursing service as well. I think I was very lucky at the time.

Although the work was not very busy, THC continued operating and little by little new projects began to come in. I stay in touch with information on aid activities for disaster victims, but I am not directly involved. I still don’t feel I have enough energy to commit to that.

The other day (January 2012), I got my first opportunity to visit the disaster area of Minamisanriku at my older sister’s request. I still didn’t feel like visiting the area damaged by the tsunami, but her push helped. I was shocked at how utterly the area I had visited so often during my school years had changed. Even so, there was already a recovery market growing and residents were pushing for the development of higher ground. Seeing such resolute action, I was struck by the desire to stand beside these people and all those like them who may not have a voice.

January 2012, Minamisanriku

Visit to Minamisanriku with my older sister, January 9, 2012

In the disaster area there are spoken things, unspoken things, and unspeakable things. In any of the three cases, there are people who continually live in the moment, together with their own thoughts. As one of those people, I tried to become closer to other people, and I am thankful that others tried to become closer to me. The feelings I felt during this disaster are probably familiar to those forced to stay in the closet while living in rural areas, or to those undergoing treatment for HIV without being able to tell anyone.

Many people from across Japan and around the world reached out to us saying that they had to do something. I appreciate your words, and it is my hope that we can together widen and deepen these bonds between us.

Contributed: October 2013

*This text is a revised version of a text written and printed in February 2012.

First printed: JAPAN Rainbow Aid, “Japan Rainbow Aid 2011 Report”

■About terminology:

In Rainbow Archive Tohoku’s “Memoirs”, there are many terms related to sexuality which may be unfamiliar. The meaning of each term is given in the broadest sense in the glossary linked below.

Rainbow Archive Tohoku glossary of terms

For more information, please visit the Sexualities and Human Rights Network ESTO or see other websites and books related to sexuality.

■About Rainbow Archive Tohoku

Our group gathers, records, and transmits direct accounts from LGBT people and people of various sexualities. By widely asserting the existence of these overlooked minorities in local communities, we hope to help people better understand their differences and find respect for each other, to create a more harmonious society for all.

Our organization was founded in June 2013 by four groups operating out of Sendai in Miyagi Prefecture: Tohoku HIV Communications, Yarokko, Anego, and ♀×♀ Ochakko Nomikai, Sendai.

Contact: ochakkonomi@gmail.com (♀×♀ Ochakko Nomikai, Sendai)

*The rainbow is used all over the world as a symbol of sexual diversity.

| Recorded on | 9 January, 2012 | |

|---|---|---|

| Recorded by | Koji Kohama | |

| Recorded at | Taihaku-ku, Sendai, Miyagi-ken and Minamisanriku, Miyagi-ken | |

| Series | ||

| Keywords |