I Started Taking Photos Again Because I Realized That the People Who Have Feelings for a Town and the People Who Lived There Need to be Doing the Documentation

March 11 Fixed-Point Observation Photo Archive Project Open Salon at the Thinking Table June 1, 2013

This article was translated by Yiyang (Ian) ZHONG, Jamie DING, John CARLYLE, Julie EMORY, Jung hun CHEON, Kenzo STURM, Linnea PEARSON, McKenna STRICKER, Minnie THOMPSON, Rebecca LEVEQUE, Tyler FRAGIE, Cindy XU, and Yen-Han NGUYEN. This collaborative translation was part of an advanced Japanese language class at the University of Washington taught by Justin JESTY.

Narrator: KUDŌ Hiroyuki

Interviewer: SATŌ Masami (NPO 20th Century Archive Sendai)

■The View from the Third Floor of the Taga Support Building the Day After the Earthquake

Photo caption: March 12, 2011, Tagajō City Central

Photo caption: March 12, 2011, Tagajō City Central

[KUDŌ:] At the time of the disaster, I was working as the director of the Tagajō City Citizen Activity Support Center (hereafter, Taga Support), a facility that opened in June 2008 to support the work of NPOs that are active in Tagajō, such as the neighborhood associations, PTAs, women’s associations, and volunteer disaster prevention. On the day of March 11, we were open as usual and there were about twenty people using the facility. The location of our office was unlikely to be directly hit by the tsunami but unfortunately we couldn't use it as an evacuation center because there was no elevator, and a large crack had appeared on the second floor. So, as the person in charge, I considered closing the facility and going to help at the disaster response headquarters but because our location was at the highest elevation, streams of people fleeing in their cars were charging up the hill in our direction and I decided to have all the staff attend to them. Fortunately, we had a minimal stockpile in the office in preparation for one of the region’s offshore earthquakes so the staff continued voluntarily late into the night, providing people with food and vending machine drinks and, so as long as the elevated water tank held out, access to the restrooms. In truth, I didn't know anything about the arrival of the tsunami because we were on high ground. We couldn’t hear any noises coming from the direction of the ocean at all. Then a clerk from the city office came racing up on his motorbike with the message that things down below were really bad so it was going to get crazy here too. When he’d left and I’d taken it in, I went down to the city office at the bottom of the hill. They had a generator so their electricity was working and when I looked at the television and saw the moment when the tsunami hit the Yuriage Bridge I knew things were going to get bad.

That night, at 9:57PM according to city records, the JX Nippon Mining Holdings Sendai Oil Refinery blew up. This photo is of the thick smoke billowing up, before the fire was put out on the 15th. This black smoke went up higher than 1,000 meters. You could see the smoke all the way from Fukuda Town if you were coming along route 45.

[SATŌ:] Were you taking a picture of the smoke? Or the parking lot?

[KUDŌ:] It’s difficult to see, but the building facing us is actually Tagajō’s water and sewage department, and below that there are people lining up for water that was being distributed. The longest wait was around five hours. They didn't have enough water supply trucks at the time, so a flower store owner in town provided a truck that was equipped with a freshwater tank and this was the scene when they were distributing water to people with that truck and the precious water supply trucks the city already owned. I took this photograph first just to document the conditions at Taga Support, but then I also felt I needed to document this scene with the black smoke rising because it seemed symbolic in some way. I took it from the stairs of the third floor fire escape.

[SATŌ:] These people here below the building are the ones lining up to receive water?

[KUDŌ:] Yes, down at the bottom there. The line continued all the way to the left and went around the back of the building, stretching all the way to the city office. The front of the line is on the right-hand side. You can see the prefab building on the right: that was where the water distribution trucks were stationed so that's what everyone was aiming for, for about five or six hours. To make matters worse, by day two telephone service was completely down, gas and water had stopped, and the power was out so each city was in a completely isolated state.

■City Office Employees Work Together with the Self-Defense Forces to Unload Aid Supplies Procured by Taga Support

Photo caption: March 15, 2011. Tagajō City Office, Tagajō City Central

Photo caption: March 15, 2011. Tagajō City Office, Tagajō City Central

[KUDŌ:] The internet and phone lines were all down, and I later heard from someone at NHK that Tagajō had become a completely forgotten city. Tagajō is next to Sendai City, but people knew even less about the situation than about Ishinomaki, so we took it upon ourselves to gather information on the damage and take it directly to NHK ourselves. As a result of Tagajō City’s zealous pursuit of administrative reforms, the number of city workers had been cut down to the limit. There were on the order of five hundred city employees in a city of sixty thousand. At the peak there were twelve thousand 3.11 refugees spread across thirty-eight evacuation shelters. I think it was extremely hard to handle with that number of people. It was a complete battlefield situation and we were left without a single person to spare to get information out to the media about our own town. We aren’t city employees, but our team went around to the disaster response headquarters and the evacuation shelters to gather information about the situation and we delivered it directly to NHK’s desk, I believe at around three in the morning. Tagajō finally made it into the news the next day and supplies then started to circulate to the shelters.

In addition, we independently contacted a foundation in Tokyo we have a relationship with and told them that we needed a truck sent to Tagajō City, whatever they had, even one ten-ton truck would help. I told them they wouldn't need to go all the way to Ishinomaki but could drop by on the way to Sendai Harbor. The truck we requested finally arrived on the 15th, and this is us all unloading it together. This was the first relief truck from a private organization.

[SATŌ:] This was the first relief truck.

[KUDŌ:] That’s right. The Self Defense Forces had separate ones of their own, but this was the first truck of non-governmental relief supplies sent to us. The shortage of resources was quite severe for the first four days, from the 11th to the 15th. The situation got so bad in some evacuation shelters that people had just a single chocolate bar for meals.

[SATŌ:] Was that because there was no information getting out about what things were like in Tagajō? Did it stem from the lack of information you mentioned just now?

[KUDŌ:] Yes. In the beginning, the very first scenes to be broadcast on NHK were of Natori being hit by the tsunami, so the resources and support vehicles converged on Natori. Next it was “Ishinomaki is in trouble!” and then "Kesennuma is in trouble!" It's strange to say, but it was like we had to compete to sell how bad the disaster was. It basically turned into a situation where nothing came unless you communicated how awful things were to the outside. In order to break through the wall, we had no choice but to put pressure on the media ourselves. In addition, we used the network we had since before the disaster in order to take control of the situation directly and that's how we got the truck to come.

■Sorting Relief Supplies to Go to Each Evacuation Center

Photo caption: March 15, 2011 Tagajō City Office, Tagajō City Central

Photo caption: March 15, 2011 Tagajō City Office, Tagajō City Central

[SATŌ:] This continues from the previous photograph, right?

[KUDŌ:] The city office workers and Self Defense Forces unloaded the supplies together. This is a photograph I took of the stage just before we took the supplies out to evacuation shelters. This is an old lecture hall on the north side of the Tagajō City Office. We spread out each of the items on blue tarps and divided them up. We generally had what the evacuation centers needed, and since they were able to communicate with the headquarters by radio, we tried our best to respond and deliver things as fast as possible according to where the high priority items were needed most quickly. Especially given the cold weather, winter clothing. And, in the case of Tagajō City, since we’re so near the coast, the winter clothing that people brought were extremely helpful: there were people who had been rescued by helicopter with literally nothing more than the clothes on their back. Diapers too. People thought to bring both the child and the adult type, which was extremely helpful.

■Conditions on the East Side of the Sendai Harbor North Interchange, National Route 45

Photo caption: March 15, 2011 Tagajō City

Photo caption: March 15, 2011 Tagajō City

[KUDŌ:] This is a photo I took at the Sendai Harbor North Interchange on National Route 45. There are quite a lot of damaged vehicles rolled over and scattered about, which I think actually attests to something unique about the tsunami damage in Tagajō City.

The tsunami was about seven meters high when it got to Sendai Port and 2-4 meters when it entered the city. But the area that got flooded was very large: thirty percent of our small city of sixteen square kilometers was flooded. There was the tsunami coming from the sea, but then also the Sunaoshi River that runs in front of Tagajō Station reversed flow and broke through its embankment, leaving the Sakuragi and Yawata districts along Route 45 caught between a tsunami coming from both the river and the sea. By the time the tsunami reached the town from the harbor its strength had weakened a little but because it churned around among the densely built buildings of the town, there was a very high number of damaged vehicles. In particular, National Highway 45 and its industrial roads alone saw 354 cars damaged in the disaster and the entire number for Tagajō City was 5,556 vehicles, including motorcycles. It was true of privately owned cars too, but the auto-related factory at Ōhira Village had just started to operate at the time, and the cars bound for export at Sendai Port were all washed from the motor pool and crashed into people’s houses. On top of that, hundreds of drums filled with concentrated sulfuric acid and other dangerous materials and more than a thousand cylinders of high-pressure gas washed into the town on the muddy flow from the factories near the coast.

I took this photo because it shows the damage from an urban tsunami and I thought that if there was an earthquake like the Great Kantō Earthquake or one along the Tonankai/Nankai Trough affecting Tokyo, Osaka, and Nagoya, it would probably result in conditions like this. Also, you can kind of see in the background there, but it was quite a shock for me to see the SDF ambulance. It was personally a very shocking photograph, seeing vehicles meant for transporting dead and wounded soldiers driving around the city streets in broad daylight.

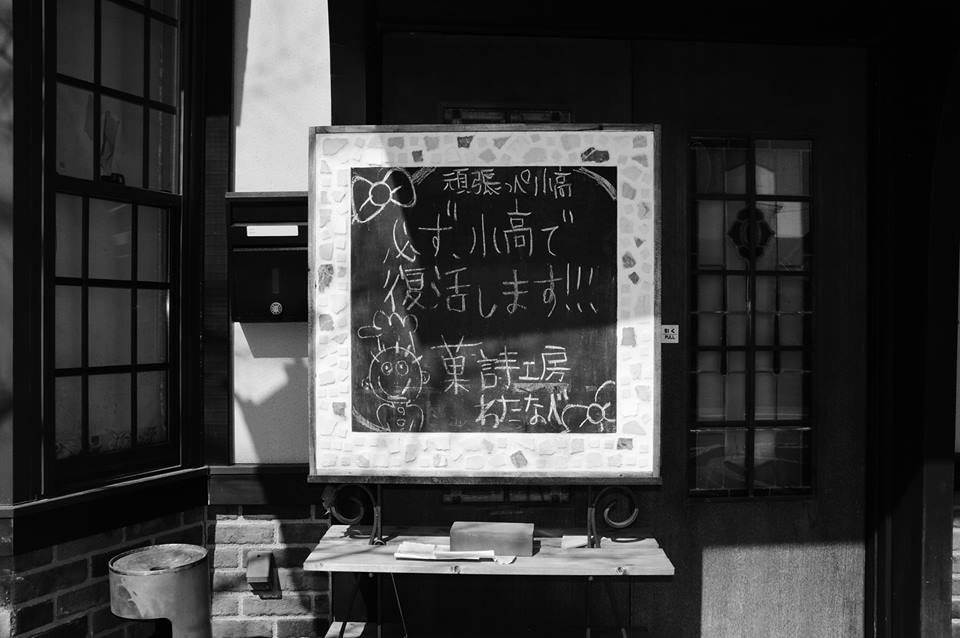

■Sweet Poetry Workshop Watanabe

Photo caption: March 22, 2013 Odaka Ward, Minamisōma City, Fukushima Prefecture

Photo caption: March 22, 2013 Odaka Ward, Minamisōma City, Fukushima Prefecture

[KUDŌ:] I have always loved the Tohoku landscape and took photographs of it as a hobby for a long time before the disaster, but personally I was no longer able to point my camera at scenes related to disaster damage. The person in charge of record-keeping at Tagajō City Office took on the task of documenting conditions in Tagajō City, and a fair number of media people began to come in, so I thought I could leave the documentation to them. I stopped taking pictures for about half a year. When we needed photographs to send information to the outside we could use ones taken by contracted professionals since we were a facility connected to the city. So I made a decision that we did not need to take it upon ourselves to photograph the damage and I personally stopped directing my viewfinder and lens at those scenes. But then, after about half a year had passed and I saw the state of things with the media, I started to feel like there were many aspects of town life that were being abandoned and forgotten, and that many things in daily life needed to be documented or spoken for. In particular, there were scenes that I hadn’t been able to photograph when I was running around Minamisōma and Namie as a company salesman and I wanted to do what I could to document them. I felt like I had to. So I started making trips to take pictures.

I took this picture on March 22 of this year in Minamisōma City, Odaka Ward. Last year on April 25, it was designated as an area preparing for the lifting of evacuation orders, so you could enter it during the daytime. Sweet Poetry Workshop Watanabe is a very famous bakery and sweets shop, with customers coming from all over the Sōsō region and even from Sendai. It cannot open now of course because the infrastructure in Odaka Ward isn’t working. Yet there in the middle of all that was a blackboard that read “We Will Reopen in Odaka, Promise” and below it were some items tucked underneath a brick: notes from passersby with messages like “Can’t wait for you to reopen” and “We’ll meet again in Odaka, promise.” Even in this difficult situation people’s feelings for the town clearly survived and I took this photo with the desire to collect that kind of sentiment.

[SATŌ:] A moment ago you said that after half a year of thinking that you didn’t need to take photos yourself, that there was something else you had to photograph, and that the reason you started pointing your viewfinder at those other things was that you had a feeling they were being forgotten in the way the media was reporting. Meaning that these are the pictures you took when you started to think that, to the contrary, there was something you were seeing with your own eyes that you needed to pass along?

[KUDŌ:] I suppose so. I didn't exactly feel like things were being forgotten, but that there were a lot of things being overlooked. There were definitely scenes that reflected what victims of the disaster and evacuees in the area were actually feeling and thinking in their daily lives but it was like the professional photographers stopped paying attention to them. It’s the people who have feelings for a town and the people who lived there that need to be doing the documentation. Otherwise those things will cease to be publicly accessible in future. So I started taking pictures like these again with the intention of doing what I could to resist or fight that problem.

■The Remains of the Railroad Crossing on the North Side of Sakamoto Station

Photo caption: November 21, 2011 Yamamoto Town, Jōban Line Sakamoto Station

Photo caption: November 21, 2011 Yamamoto Town, Jōban Line Sakamoto Station

[KUDŌ:] It’s hard to see because the photo ended up being a bit high contrast, but this is a picture I took at a railroad crossing two stops away from Sakamoto Station in Yamamoto Town on the Jōban Line. There was this sign standing there that took my breath away. “105 years of service, the ground is solid, 70 tons of locomotive.” When I looked into it, I found that steam locomotives used to run here in the old days. It may have been an elderly person who knew the history or someone who had been a railroad worker, lodging their plea for the Jōban Line’s recovery. In fact this wasn’t the only such sign: there were similar signs standing at several other crossings. I had the feeling that what had suddenly appeared to me in the form of this sign were all of the memories, all of the feelings, all of the cherished feelings that were sleeping there in the middle of nowhere in this seaside town of Yamamoto that had turned into a complete wasteland. This is one photo I took thinking I just have to get this.

[SATŌ:] Thank you very much. There is part of me that has always felt that photographs of how people lead their lives amidst disaster are important. I think that statistical records and documentation of disaster conditions will always remain as documentation but that it’s memory that really works to communicate effectively as an image that can jolt and sway the emotions. Like this sign, for example, photos that show what life was like in the midst of the disaster, or the one showing people lining up to receive water just a bit ago, or the photos taken by others with people lining up for gas, and emergency food rations, there was a lot of standing in lines, and if you were a person from an affected prefecture everyone knows about it and it seems obvious, but if you go further away on the other side of Tokyo people don’t know and think, “Oh, is that what it was like?” There are times when I come back from touring with the photographs that I acutely feel that the problem arises because people have only ever seen images of the tsunami and things that collapsed in the earthquake. Your talk also made me think along these lines, that the question of how to preserve our memories is extremely important.

* This article is based on the contents of KUDŌ Hiroyuki’s talk at the “March 11 Fixed-Point Observation Photo Archive Project Open Salon ‘Continuing to Watch, the Scenes from that Day,’” held at Sendai Mediatheque’s Thinking Table on June 1st, 2013.

[March 11 Fixed-Point Observation Photo Archive Project]

This project archives citizens' documentation of the circumstances right after the disaster, and the circumstances of the subsequent reconstruction and recovery through periodic fixed point observation in the cities and towns of Miyagi Prefecture that were affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, in order to leave them to posterity. We continue to gather documentarists from among the citizens, and periodically host spaces for information exchange and other activities in the form of Open Salon. These fixed point observation photos are stored and published in both the 20th Century Archive Sendai and the center for remembering 3.11(sendai mediatheque), as a part of “Records of the Great East Japan Earthquake -Citizens’ Collaboration Archive”.

website: http://www.20thcas.or.jp/

[Thinking Table]

The Thinking Table is our name for a space where people can get together and share stories, and think about disaster recovery, the regional community, and expressive activities. It is held in the studio on the 7th floor of Sendai Mediatheque. There are a variety of events including talks, public meetings, and activity reports by citizen groups.

| Recorded on | March 12, 2011 - March 22, 2012 | |

|---|---|---|

| Recorded by | KUDŌ Hiroyuki | |

| Recorded at | Tagajō City, Miyagi | |

| Series | ||

| Keywords |