Hamagurihama

Oshika peninsula rephotographed, part 2

March 17, 2024

This is the second of two reports revisiting images made for the Recorder 311 project on July 16, 2011 by Izuru Echigoya, a project staff member at the time. Whereas Echigoya-san found Hamagurihama by accident after getting lost, we had every intention of coming across it. Having first gone to Orinohama (link), and traveled further on to Kodakehama (out of curiosity) we stopped at Hamagurihama on our way back to Ishinomaki city.

We were here to rephotograph locations in Echigoya-san’s images, but in contrast with Orinohama, Hamagurihama also felt as though stories were also in the air. That we could park the car in a designated area suggested visitors had always been and were always hoped to have a role here. True enough, I later learned of the beach’s original sandy reputation along with the village’s close-knit spirit, and then of the collective trauma of 2011 and subsequent drive of remaining residents to bring life back. On another day and with more time, we would likely have visited the Hamagurido café overlooking our parking spot.

We began our activities with an image of what appeared to be a shelter for a bus stop. We are yet to learn the full story of this shelter, but historical imagery via Google Street View shows that the shelter was moved to the other side of the street within two years of Echigoya-san’s visit, which was how we still encountered it. During our visit, the former position of the shelter had become home to a no-parking traffic cone and a sign warning against poaching. The change in direction of this shelter was curious and encouraged one to casually speculate about relationships with the sea: first shunning it and then embracing it –– but (again) that is mere speculation on my part. What was not speculation, however, was the thought of waiting at the shelter for public transport: just as with Orinohama, there is only one bus in and one bus out.

We began our activities with an image of what appeared to be a shelter for a bus stop. We are yet to learn the full story of this shelter, but historical imagery via Google Street View shows that the shelter was moved to the other side of the street within two years of Echigoya-san’s visit, which was how we still encountered it. During our visit, the former position of the shelter had become home to a no-parking traffic cone and a sign warning against poaching. The change in direction of this shelter was curious and encouraged one to casually speculate about relationships with the sea: first shunning it and then embracing it –– but (again) that is mere speculation on my part. What was not speculation, however, was the thought of waiting at the shelter for public transport: just as with Orinohama, there is only one bus in and one bus out.

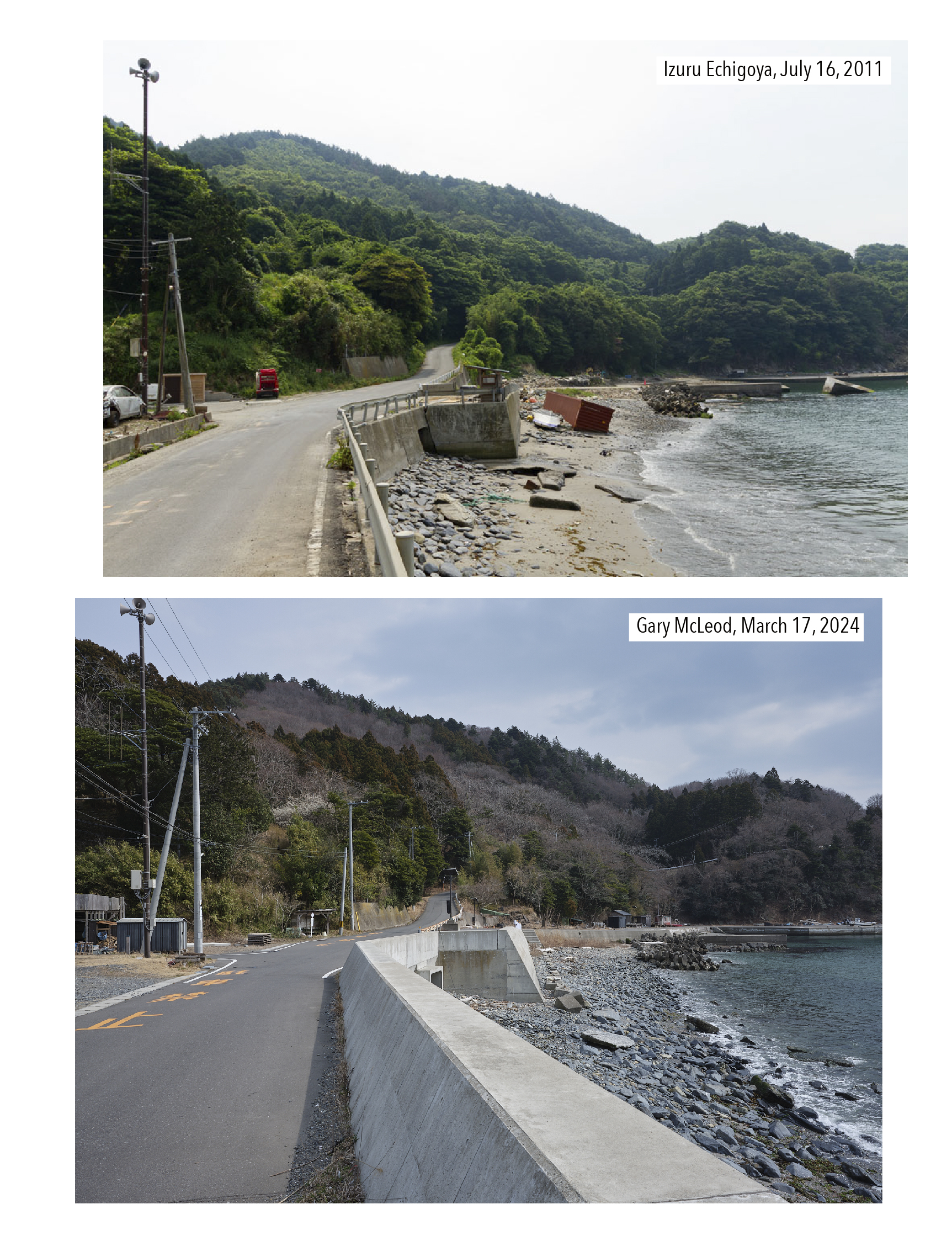

Our attention turned next to a wider view that Echigoya-san made of the shoreline (note, we did not rephotograph the images in the same order). The shelter is visible in the center of the image, as is the access road. No clearly defined sea wall was in effect in 2011; only a metal railing divided the road from the beach, although the road was elevated from sea level (it’s the same kind of road-beach division seen in my hometown in the UK). Our visit confirmed a newer concrete wall structure akin to other shorelines of this region, albeit one considerably shorter. Comparing both photos, the newer structure felt like a reinforcement rather than additional protection. Lining up my frame to echo the original highlighted continuities: for example, the position of the utility pole to the left, the access road at the back and its retaining wall, and the tetrapods to the center-right. But the comparison also drew attention to the slabs of concrete on the beach: could they be the same ones? Perhaps not, but we were now engaged in an act of looking (and wondering).

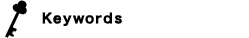

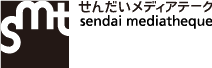

Walking into that frame took us along the shore and to a view Echigoya-san made of the concrete jetty that had been broken by tsunami in 2011. Not achieving the exact vantage point presented a problem of visually conveying whether the jetty had been restored or left as it was. Historical satellite imagery via Google Earth’s desktop application suggested the jetty was not restored to its original length. Therefore a decision was made to align both images according to the position of what remained. Doing so drew attention to the pieces of concrete removed. Echigoya-san had also made a second image from the end of the jetty. Reluctant myself to step down onto the concrete, I flew a drone over to Echigoya-san’s presumed vantage point. The edge of the concrete clearly remained in the same condition, albeit with markings weathered away. A dark shape also remained beneath the surface of the water. All that appears to have gone is the broken piece itself; a reminder that fragments are either seen as signs of destruction or romanticist expressions of the picturesque. For purely aesthetic reasons, part of me wanted that fragment to still be there.

Continuing to walk further along the shore revealed various huts, cabins, and shelters of differing conditions and purposes, some more grandiose than others: communicating how this beach has variety in its visitors.

The last of the images in this report is a composite that is less a precise rephotograph of a vantage point and more a rephotograph of the experience of looking down from the water’s edge. Whereas Echigoya-san pictured sea, sand, and detritus; my frame was notable for the volume of shells left behind in the sand by the tide. While many shells appeared to be shucked oysters, a washed-up glove served enough of a reminder that this beach has a past with or without images.

※These rephotographs were produced during fieldwork funded by the DNP Foundation for Cultural Promotion.

Previous page

Orinohama: Oshika peninsula rephotographed, part 1

Related posts

Orinohama, Ishinomaki, Miyagi

Hamagurihama, Ishinomaki, Miyagi: A Quiet Sea

| Recorded on | March 17, 2024 | |

|---|---|---|

| Recorded by | Gary MacLeod | |

| Recorded at | Hamagurihama, Ishinomaki, Miyagi | |

| Keywords |