The Bonds of a Gay Person

Written by: Futoshi

Born and living in Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture

Gay since birth. Late 30’s at the time of the earthquake.

Representative of community center ZEL (*1)

Representative of volunteer group Yarokko (*2)

■March 11

The big quake came when I was at my workplace in Natori. The building was made of old reinforced concrete, and as the stairs and ceiling seemed about to collapse we all waited for the shaking to stop before taking refuge in the parking lot outside. From the neighboring building I could hear the incessant, shrill ringing of an emergency bell. My phone wouldn’t connect, so I turned on the car radio and learned of the imminent risk of a tsunami. My workplace is located in Natori, but in an area far from the coast. Even so, we were standing near the river, and so we all decided to immediately take refuge.

I headed straight for my home in Sendai by car. The gate at the railway crossing was down, and the signals were off due to the blackout. As I drove, I plotted a route in my head that crossed the fewest intersections possible. I had been planning to get gas on my way home and the needle on the gauge was pushing past the “E”, but luckily I found a gas station on my way which had a line of cars. I was told that they were out of regular gas but I could fill up with 20 liters of high octane. Because the power was out, the attendant had to pump up the gasoline by hand while sweating profusely. I was overcome with gratitude at the sight. I had been listening to the radio, but there was no information about the damage caused by the tsunami, nor did I know how much damage had been caused across the city. As a result of this lack of information, the most trivial concern occurred to me: I had planned to go to a friend’s farewell party that evening and stay over at a hotel with two other people, but I was now unable to contact the hotel to cancel; would we still be charged for the room? (I later learned that the venue reserved for the party was located in a building which was later torn down, and my friends who had been unable to return home had stayed in the hotel after, so the room didn’t go to waste.)

Upon arriving home, my elderly mother and my nephews who lived in the neighborhood began telling me excitedly about what had happened during the earthquake. Thankfully the stories were nothing more serious than a fallen light fixture, objects falling from shelves, and a cracked wall. The power and gas were out, but we still had running water.

The whole family gathered at our house, and we began living together as one big family: me and my mother, my two older sisters and their husbands, and my four nephews, for a total of 10. We brought out our emergency reflective heater for cooking, and because we had to finish off all the food in our freezer before it rotted due to the blackout, that night we had a sumptuous dinner.

I was able to receive texts on my cell phone, but I could neither send texts nor make calls. I received many texts from people telling me they were okay, but I couldn’t reply. I was able to browse the internet, so I posted on mixi and other SNS that I was okay and that “community center ZEL” (“ZEL” below) would be on hiatus. I also used the communication feature in a mobile game to tell my boyfriend in Tokyo that I was alright. I dislike games, and so I never imagined that the mobile game that my boyfriend forced me to try would be useful in such a way.

■March 12

On my way home from work, I went to check in on ZEL. Upon arriving at the building in which ZEL is located, I found that the elevator had not yet been restored and was still unmoving. I climbed the stairs to the 9th floor only to discover that I had forgotten my key. With nothing else to do, I peered through the glass door of the neighboring computer lab, only to be greeted by the sight of computers strewn about the floor. Everything was overturned as though Heaven and Earth had been turned upside down.

■March 13

ZEL’s staff, volunteers, and I went to tidy up at its offices. As before, the elevator was still out and I arrived at the 9th floor covered in sweat. We opened the door to find only chaos.

The legs of desks had bent, and computers and TVs had fallen to the floor. Even the contents of chests of drawers were scattered about the floor as though someone had ransacked the place. A kettle and a humidifier had fallen over and the floor was soaked with water. Nevertheless, the computers and TVs which had fallen to the floor were not entirely broken. The kettle, too, hadn’t cracked. It was a miracle that although so many things had fallen almost none of them were broken.

It took three of us a whole day to restore the place. I spoke to the staff and we decided that because transportation was still unstable we would not open on Monday the 14th. Rather, we would keep an eye on the status of transportation and the elevator’s restoration of operations, and we would consider when to reopen.

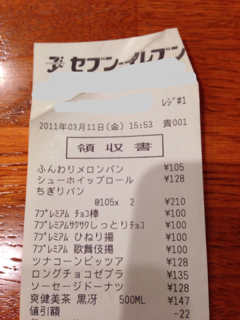

March 13, 2011, AM: community center ZEL, 3-3-5 Kokubuncho, Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture

March 13, 2011, AM: community center ZEL, 3-3-5 Kokubuncho, Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture

■March 16

We decided to reopen ZEL on the 18th. We posted a notification on our homepage, which read: “Reopening on Friday the 18th. One of our two heaters is broken, but we will be serving hot beverages. All LGBT people who have been affected by the disaster, please come and gather.”

■March 17

On ZEL’s homepage and mixi we began posting the following notices: “To those people taking anti-HIV medication who have been affected by the disaster” We advised people to call their primary care doctor or a help line and ask what to do if they became unable to take their medication. (The standard explanation is that if someone taking anti-HIV medication forgets to take it, the virus develops a resistance to the medication and it no longer works.) The next day we updated the information and posted a link to the procedure for dealing with such a situation which had been posted by a medical institution.

■March 18

We reopened ZEL as planned. Although transportation had not been completely restored yet, 8 people visited our offices. Someone brought lots of rice balls they had made at home, and someone else brought a bunch of snacks they’d gathered from their house. I was grateful for everyone’s kindness.

Some people had lost their homes or their parents’ homes while others were still unable to contact their dear friends, but we all gathered together and shared our stories for a little while.

I, too, was unable to contact my friend who worked in a coastal town. When I called my friend’s boyfriend, all he could say was, “I believe he’s alive.”

■March 19

One after another, I received messages from friends whom I had been unable to contact.

I received a text from my friend working in the coastal town, saying “I was hit by the disaster, but somehow I’m still alive.” “I’m so glad you’re alive,” I replied.

My friend from Kansai texted me: “Sorry for not texting sooner. I’m okay. How are you doing?” “I’ve been hard at work since the day of the earthquake,” I replied. To which he responded encouragingly, “Same here. We’re still alive, so let’s give it our all to help the rebuilding. We can do it!” He had lived through the Great Hanshin Earthquake, and his inimitably vigorous reply gave me strength.

I even received a text from a friend I hadn’t heard from in about ten years. Out of the blue I got a text saying “I saw your picture on mixi for the first time in a while; you’re looking old.” Now that I thought about it, he was living in Natori, too. When I asked what his status was, he replied, “My house was swept away by the tsunami, so I’m living in an evacuation center now. There’s nothing to do at night and I’m bored, so I’ve been going through my address book from top to bottom and texting everyone.” I admired my friend’s strength to be able to make me smile with such cheerful messages even as he was living in an evacuation center.

■March 21

We posted online that we would be holding our Gay Night (an event for gay men only) in May as scheduled. We had considered canceling it, but people told us that after the disaster they hadn’t been able to see any of our people (gay people) and were feeling lonely, and that especially at a time like this they wanted a chance to get together, so we decided to go ahead as planned. Guests from Tokyo, Osaka, Nagoya, and all over the country said they would be there.

Many other things happened besides.

I sent a text to an expat I knew who lived in my neighborhood but spoke no Japanese asking, “Are you OK?” He responded that he was in dire straits, saying, “I am OK but no water, no food.” Because he spoke almost no Japanese, he had been unable to obtain any information. There was a water truck at the university right next to his house so I told him to bring a bottle to get some water. I also did my best to send him information in broken English about supermarkets which were open, and gave him a phone number for a disaster information line for expats.

An online gay dating bulletin board site was inundated with messages from people checking on each other, encouraging each other, and sharing information about gas stations and supermarkets. The bulletin board operator set up boards specifically for checking on each other’s safety and exchanging support information. People outside the disaster area and heterosexual people would have no way of knowing that a dating bulletin board site was put to use in this way.

The ZEL staff member was from Ishinomaki and had lost many relatives, neighbors, and friends to the tsunami. He had made it a daily task to check the list of the lost in the newspaper, but he said that “I counted up to 70, but there was no end so I just stopped counting.” I suggested he go back to visit his hometown, but after seeing images in the newspaper and on TV of the utter destruction wrought upon it, he said, “I don’t want to see my hometown with everything gone.” And so he continued to keep ZEL open tirelessly and smiled at every person who came into the offices.

When I was first asked to write about the experiences of LGBT people during the disaster, I thought I didn’t have much in particular to write about. But once I started writing, I remembered that a lot really did happen.

Looking back, I never felt that I had difficulties because I am LGBT, but there were times when I felt the special bonds of the LGBT community. ZEL received donations from LGBT communities in Tokyo, Okinawa, and Taiwan, and people from all over the country came to help us rebuild. I also started visiting my friends in Fukushima more than I had before the earthquake, and I had more opportunities to go to gay events there as well. If I were a heterosexual person, I don’t think I would have friendships spanning across Japan and even overseas. The bonds which I probably would not have felt were I straight were what I felt most strongly throughout the disaster as a member of the LGBT community.

*1: community center ZEL

A center for information on HIV for gay and bisexual men, located in Kokubuncho, Aoba-ku.

Operated by the Japan Foundation for AIDS Prevention (commissioned by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare).

*2: Yarokko

A volunteer group based in Sendai which provides accurate information about HIV/AIDS to the gay community in the Tohoku region. The group operates in partnership with community center ZEL and also hosts events to spread awareness of HIV/AIDS, as well as developing and distributing informational materials.

■About terminology:

In Rainbow Archive Tohoku’s “Memoirs”, there are many terms related to sexuality which may be unfamiliar. The meaning of each term is given in the broadest sense in the glossary linked below.

Rainbow Archive Tohoku glossary of terms

For more information, please visit the Sexualities and Human Rights Network ESTO or see other websites and books related to sexuality.

■About Rainbow Archive Tohoku

Our group gathers, records, and transmits direct accounts from LGBT people and people of various sexualities. By widely asserting the existence of these overlooked minorities in local communities, we hope to help people better understand their differences and find respect for each other, to create a more harmonious society for all.

Our organization was founded in June 2013 by four groups operating out of Sendai in Miyagi Prefecture: Tohoku HIV Communications, Yarokko, Anego, and ♀×♀ Ochakko Nomikai, Sendai.

Contact: ochakkonomi@gmail.com (♀×♀ Ochakko Nomikai, Sendai)

*The rainbow is used all over the world as a symbol of sexual diversity.

| Recorded on | 13 March, 2011 | |

|---|---|---|

| Recorded by | Futoshi | |

| Recorded at | 3-3-5,Kokubunchou, Aoba-ku,Sendai-shi,Miyagi-ken | |

| Series | ||

| Keywords |