Realizing Nothing Would Get Moving If I Didn’t Bring Back the Right Information, I Went Out With My Camera

March 11 Fixed-Point Observation Photo Archive Project Open Salon at the Thinking Table June 1, 2013

This article was translated by Yiyang (Ian) ZHONG, Jamie DING, John CARLYLE, Julie EMORY, Jung hun CHEON, Kenzo STURM, Linnea PEARSON, McKenna STRICKER, Minnie THOMPSON, Rebecca LEVEQUE, Tyler FRAGIE, Cindy XU, and Yen-Han NGUYEN. This collaborative translation was part of an advanced Japanese language class at the University of Washington taught by Justin JESTY.

Narrator: KOCHIZAWA Masayuki

Interviewer: SATŌ Masami (NPO 20th Century Archive Sendai)

■After Raking Up the Sludge

Photo caption: March 12, 2011 Arai, Wakabayashi Ward

Photo caption: March 12, 2011 Arai, Wakabayashi Ward

[KOCHIZAWA:] I was living a very noncommittal lifestyle at the time of March 11, half in Sendai City and half in Sakata City in Yamagata Prefecture. It had been nine days since we had discovered my wife was pregnant, making it a very unsettled time for me. While trying to stay in Sendai as much as possible I was going back and forth to Sakata, and on the day of March 11 I was checking emails in front of my computer back in my faculty office in Sakata when there was a large earthquake. I had felt the large earthquake two days prior but it was nothing compared to the shaking this time, even though I was far off in Sakata. I knew intuitively that this spelled trouble for Sendai so after making sure my students were safe I hurried to get back there. Snow had started to fall in Sendai and the Shōnai region has exactly the same climate. Filled with uncertainty, I was able to make it back to Sendai during the night but even then I was still not able to confirm whether my wife’s family was safe.

Speaking of which, as you can see clearly from this first picture, although my in-laws’ house is in Sendai City, it’s about half a kilometer from the Sendai-Tōbu Road on the seaward side, and while it looked like the tsunami had definitely reached there, we didn’t know any details. The next anxious morning dawned without us learning much. It took two hours to drive from central Sendai out to the coast. I can remember how chaotic the city was. This was the second or third picture I took after we arrived. I actually took a few thousand photographs subsequently, but at that time around March 12 I didn’t feel right taking photos of people. My own family had been affected by the disaster, yet even with them it felt wrong to be pointing a camera at people. This is one of the pictures I took when I was feeling that way. It’s a photo from when things were in disarray, when my family had raked up a fair amount of sludge but there was still a lot of work to be done like picking up all the furniture that had fallen down.

[SATŌ:] You shared this same story when we published 3.11 Kioku no kiroku: shimin ga totta 3.11 daishinsai kioku no kiroku (Recording the memories of 3.11) (Footnote 1) about six months after the disaster. You explain everything exactly the same way you did then. As I was listening I thought your memory hasn’t faded a bit. You may have skipped over some parts in the middle because of time but I am impressed by how consistent you are.

[KOCHIZAWA:] Well, it was something that happened when we had just found out we were going to have a baby so given those special circumstances it may well have been easier for things to stick in my memory. I felt terribly guilty about having been in Sakata, for about a year after the disaster. I was born in Sendai but lived in Iwate Prefecture from age one to nine, so I didn’t experience the 1978 Miyagi Earthquake, nor the main shock or the foreshocks of this earthquake. As someone who works in urban planning and community development, I knew that as someone on the ground there were aspects of the situation I needed to explain. But even with my family being victims of the disaster, I feel like the guilt of not having directly experienced the quake drove me in the direction of gathering as much information as I could.

■Independently Owned Stores Are the First to Open and Provide Goods

Photo caption: March 17, 2011, Sendai City, Wakabayashi Ward

Photo caption: March 17, 2011, Sendai City, Wakabayashi Ward

Used in the exhibition “March 12: The First Meal After the Earthquake—When,

Where and What Did You Eat?”

[KOCHIZAWA:] I went to my in-laws’ house every day for a few days, as we raked up mud and put the furniture back in place. Except for one day—I think it was the day the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant blew up and they told me not to come—I got completely covered in mud as we raked it up. Even though the tsunami had caused some damage to my in-laws’ home they were just about able to carry on normal life. They live on a farm so they had a generator and gas and we could make as much electricity as we needed if we used the fuel. I went back and forth every day, taking advantage of this blessing.

In meantime, going back to life in the city, I think everyone had a rough time for the first 2-3 weeks as food steadily ran out. This is a photo I took on a street I passed by during that time. There was part of me that was really impressed by how store owners stepped up to do their work for others even though everyone was searching for food at the time and one’s own family comes before everything else.

[SATŌ:] After you had come back to Sendai from Sakata how long did you stay in Sendai?

[KOCHIZAWA:] I only had enough gas to make a one-way trip back to Sakata. And a few days after this on March 23rd, I set off back to Sakata with the knowledge that I might not be able to return for a while.

[SATŌ:] People can understand from this photograph how independently owned stores were the quickest to reopen. Whenever I show people this photo I contrast it by showing it together with a photo of a convenience store. When those convenience stores that are supposed to be open 24 hours a day, 365 days a year shut down, it turned out that it was these independent stores that that people don’t usually shop at and close up early that were actually helpful at a time like this. They opened up the quickest and provided food to citizens of the city. Food is one of the most intimately connected things to daily life, as is the way these independent shops reopened, and I wonder if that was what made you take a picture of it.

[KOCHIZAWA:] Ah, I see. I don’t think I was thinking about it that deeply. It was just a picture I took out of surprise that there was a store open. I mean it’s like you just said. No matter how much I walked around the city after this, all of the chain stores remained closed and even if they were open you had to stand in a huge line to get anything. We all experienced that for the first two weeks. Compared with that, I guess you could call it hustle, but there really are things you can do when you’re there on the ground, like you said.

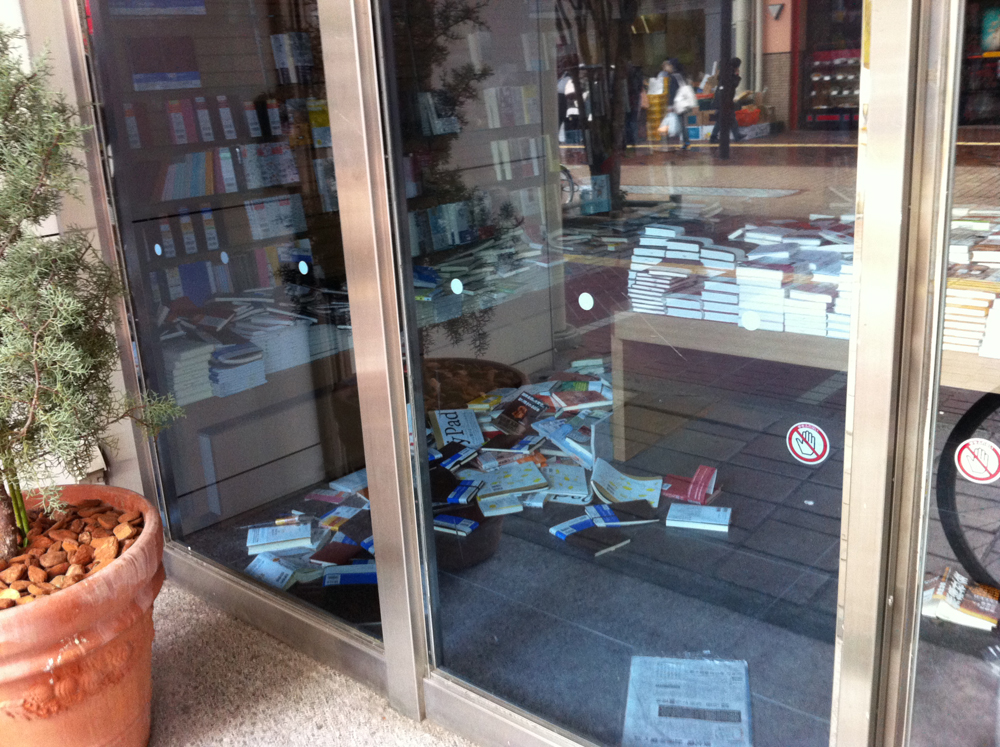

■A View of Sendai City’s Downtown Shopping Arcade

Photo caption: March 18, 2011 Sendai City, Aoba Ward

Photo caption: March 18, 2011 Sendai City, Aoba Ward

[KOCHIZAWA:] I was also actually feeling guilty about not being able to return to my university, and I was wondering whether it had been a good decision to stay in Sendai and whether there weren’t things I could do while I was in Sendai. I started having email discussions about it with my university colleagues around March 16.

There were basically two things we were anticipating. One was that there might be something the university could do for the affected areas. The other was that there would probably be quite a large number of people evacuating from the affected areas to Yamagata Prefecture including the Shōnai region, and in reality that had already started to happen. This connects to my next photo as well, when I visited Sendai City Office to consult about whether there was some way we could collaborate. When I went to meet with them I took the opportunity to have a look around the city. Having been shut away at home for so long facing off with the tsunami mud day after day, one thing that totally surprised me was how bustling the shopping arcade was. There were huge numbers of people walking around and, while most of the stores are closed, the local shops had taken the initiative to put out tables and serve take-home miso soup and rice balls, even after more than a week had passed since the earthquake. It somehow gave the city a sense of security. It was a moment that made me feel the city’s doing all right, that it will be OK.

I saw one thing that stood out in the opposite direction and I took a photo of it too: a bento store selling cow tongue takeaway lunches for ¥1,000 each. It made me think that if businesses are raking it in like this even at a time like this then the city’s going to be just fine. Almost all the stores in the arcade were closed temporarily, and it looked like they were in no shape to be able to open. But still, the contrast with so many people walking around was striking.

■Newspapers Posted on the First Floor of Sendai City Office

Photo caption: March 18, 2011 Aoba Ward Sendai City

Photo caption: March 18, 2011 Aoba Ward Sendai City

[KOCHIZAWA:] This is a photo from when I went to consult at Sendai City Office like I just mentioned. It was pretty chaotic in the city office too, and the department I went to consult with was the very same one managing disaster shelter operations so I saw with my own eyes the dire state the employees were in after working through many nights with no sleep. Along the same lines, the auditorium on the 8th floor had been opened as an evacuation center and as of that day, March 18, there were many people staying overnight over there. During the period of time when there was no electricity, people were saying that radio was a very important source of information, but for me actually the tool that had the biggest impact was newspapers. I spent an anxious night on the night of the earthquake with no electricity or information, but at dawn the next day when I looked into the mailbox there was the March 12 newspaper, all delivered. I thought it was amazing—I was honestly inspired. Who had been able to do this? Everyone had suffered from the disasters but they still delivered us information like this. It was incredible. They’re a medium you can take your time to read through carefully. You won’t miss hearing something like on TV or radio because it stays there in the print. No matter where you went there were newspapers posted like this. I had the feeling with this photo that they’re one of the most important sources of information.

[SATŌ:] I didn’t know there were newspapers posted at the City Office until I saw your picture. I have seen a picture of newspapers posted on the corner of the Fujisaki department store with a lot of people looking at them but I didn’t know it was the same at the City Office too until I first saw your picture.

[KOCHIZAWA:] I can’t imagine in any simple way what people’s lives must have been like as they sought information in this way—all the city residents there, probably including some of the people sleeping on the 8th floor. But I could understand how important information is for everyone. My wife’s parent’s home used to have newspapers delivered by a shop in Arahama, but all the newspaper shops there got washed away so they didn’t receive a newspaper for two or three weeks. In many of the disaster-hit areas people passed the time after the disasters without any print media. For me the newspapers were really important.

■Yuriage Harbor Morning Market Reopened Two Weeks After the Disaster (Aeon Mall Natori)

Photo caption: May 3, 2011 Moriseki no Shita, Natori City

Photo caption: May 3, 2011 Moriseki no Shita, Natori City

[KOCHIZAWA:] This is the Aeon Mall in Natori. I felt up for going on a little excursion over the Golden Week holidays, so I went there with the idea of checking out how the city was doing while also getting some shopping done. They were holding an event in the parking lot to provide second-hand clothing to victims of the disaster. There were quite a lot of cardboard boxes there, so they may well have received a large number of them from around the country. This is a picture I took not really able to imagine how everyone in Yuriage had been getting by since the disaster, nearly two months prior. At that moment I was thinking about how this huge shopping center could turn into more than just a commercial space: when something happens, it could be a gathering place for people. There was a stage event happening nearby with musicians performing in order to lift the spirits of those that’d been affected by the disaster, though I couldn’t tell if it was business or genuine volunteer spirit. But the sight of this run-of-the-mill commercial space taking on a different form and function was something that, while it might not be entirely appropriate to say, I thought I could make use of later, so I wanted to document it properly.

[SATŌ:] You were talking earlier about having a sense of guilt because you didn’t experience the disaster, but I guess it wasn’t only that since working in the field of community development and having that way of thinking also connects to your motivation to take photos of things like this.

[KOCHIZAWA:] I got into the habit of taking my camera with me whenever I go out and I still carry that same camera to this day. It’s heavy so I don’t like carrying it around if I can get by without it, but you never know when something might happen and if you stumble upon something it’s the best tool for communicating with people about it. In this instance too, I had gone out shopping with my wife but I remember asking her to wait just a sec while I took a few pictures and then we carried on.

■Post-Disaster Conditions in Shiogama City

Photo caption: March 24, 2011 Minatomachi, Shiogama City

Photo caption: March 24, 2011 Minatomachi, Shiogama City

[KOCHIZAWA:] With this photo, I was intrigued by why you chose it and whether or not you remembered me saying something about it to you. About how I’d gone back to university in Sakata but came back to Sendai after staying just one night there. Fortunately there was a place on the way to Sakata where I was able to get gas so I made it back after one night without any trouble. Until that point I had been wary about poking around, even in the area around my in-laws’ house. Many people had passed away within just a few minutes’ walk. In all honesty, I wasn't enthusiastic about seeing what conditions were like. Although I wasn't enthusiastic about it, the truth is that I had had a very bad experience in Sakata. When I talked to my colleagues about the disaster, their sense of it was completely different from mine. The students and other faculty had no sense of urgency at all, like they were just waiting around calmly for someone to come and tell them how they could help.

I thought this was no good. Realizing nothing would get moving if I didn’t bring back the right information, I took half a day to walk around some of the coastal areas. That was on the 24th.

I started from Sendai City and headed towards Tagajō and Shiogama, staying on the industrial roads. I think this is the place I finally got out of my car for the first time and took pictures. This is one photo that had a tremendous impact on me, or rather, my time in Shiogama made a huge impression on me, and as someone who works in community development and urban planning, I had to collect these materials to communicate it to others. Even more than that, I had gone out with my camera with a sense of mission, feeling really disturbed at the difference in intensity that was developing between affected areas and other cities, not even two weeks since the disaster. It was right about when I took this photo I think, that some volunteers who were raking up mud at the site came towards me with a very threatening attitude and shouted, “What the hell are you doing” and “This isn’t the time to be taking pictures.” It was a really complicated situation. It’s an indisputable fact that a lot of people were coming into the area to sightsee at the time. The people who had come to help clean up the sludge, sometimes from a long way away, naturally felt antipathy towards them and when they saw people doing it they thought it was ridiculous. But at the same time, how could I document this moment of the town? This picture made me ponder how to best preserve documentation without burdening all those affected by the disaster. The way I took pictures changed dramatically after this. This picture really made me think about how to do it best.

[SATŌ:] That is the first time you’ve shared that with me. The reason I chose this photo was that I tried to go to the same place to do fixed-point observation but I had some trouble finding the spot. And then I started to wonder why you took a photo at that spot, why you were there. When you sent us the images this was the first one I wanted to ask you about. I had no idea there was that kind of back story behind it. You mention that you were wondering if there was a way to take photos without being a burden and that you changed the way you took pictures—that was the result of this incident?

[KOCHIZAWA:] That’s correct. It’s from that point that I began to be as transparent as possible about who I was and what I was doing and to be really careful about asking permission before taking any photographs with people in them, especially in places where there were volunteers or disaster victims.

* This article is based on the contents of KOCHIZAWA Masayuki’s talk at the “March 11 Fixed-Point Observation Photo Archive Project Open Salon ‘Continuing to Watch, the Scenes from that Day,’” held at Sendai Mediatheque’s Thinking Table on June 1, 2013.

[March 11 Fixed-Point Observation Photo Archive Project]

This project archives citizens' documentation of the circumstances right after the disaster, and the circumstances of the subsequent reconstruction and recovery through periodic fixed point observation in the cities and towns of Miyagi Prefecture that were affected by the Great East Japan Earthquake, in order to leave them to posterity. We continue to gather documentarists from among the citizens, and periodically host spaces for information exchange and other activities in the form of Open Salon. These fixed point observation photos are stored and published in both the 20th Century Archive Sendai and the center for remembering 3.11(sendai mediatheque), as a part of “Records of the Great East Japan Earthquake -Citizens’ Collaboration Archive”.

website: http://www.20thcas.or.jp/

[Thinking Table]

The Thinking Table is our name for a space where people can get together and share stories, and think about disaster recovery, the regional community, and expressive activities. It is held in the studio on the 7th floor of Sendai Mediatheque. There are a variety of events including talks, public meetings, and activity reports by citizen groups.

| Recorded on | March 12-May 3, 2011 | |

|---|---|---|

| Recorded by | KOCHIZAWA Masayuki | |

| Recorded at | Sendai City, Wakabayashi Ward | |

| Series | ||

| Keywords |